Respect where it’s long overdue.

The other day, as I wandered through my neighborhood in Seoul, I noticed a group of middle-aged Korean women sitting together in front of small shops, chatting and laughing in high spirits.

Later, in Busan, I saw pairs or trios of similar women navigating the crowds with shopping carts — cutting queues, edging into elevators, claiming their seats in the bus. Their behavior startled me at first: so direct, almost defiant. Yet although rather short in stature, they moved with unmistakable strength and purpose — clearly headed somewhere, and heaven help anyone standing in their way.

When I described these scenes to a friend who’s lived in Korea for years, she smiled knowingly. “You’ve just met ajummas,” she said — and with that single word, a whole world of meaning opened up.

MEET THE AJUMMA

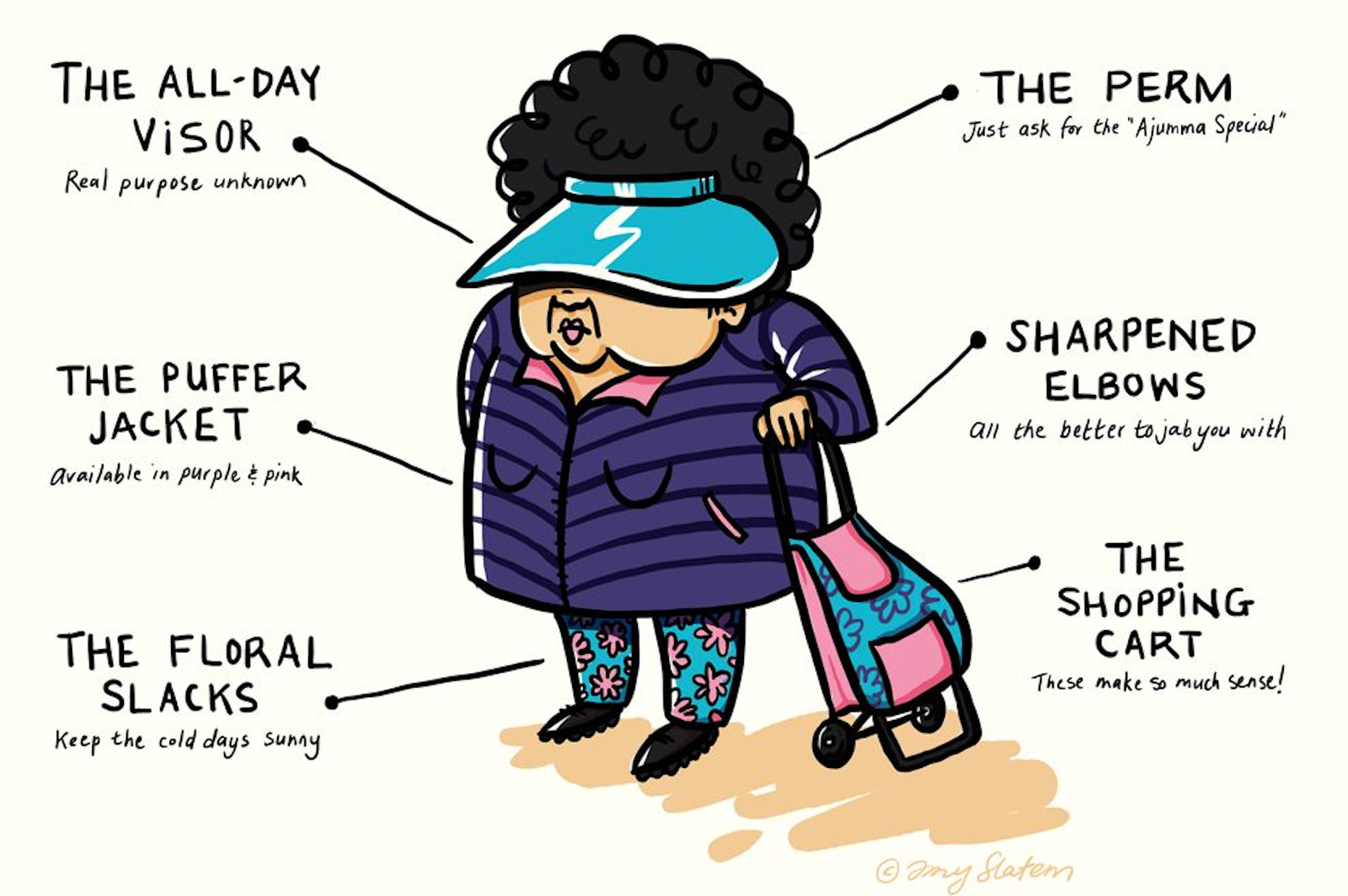

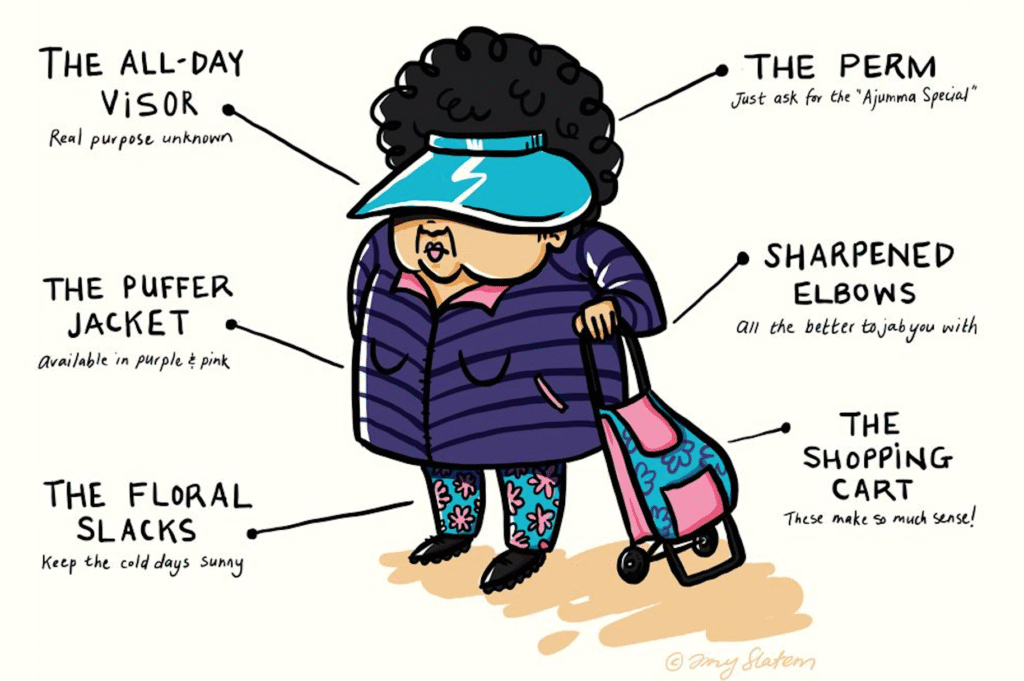

Illustration from Amy Slatem on Art Aims ©

What is an Ajumma?

In Korean, ajumma (아줌마) are married or middle-aged woman. It comes from ajumeoni (아주머니), a polite way to say “madam.” Over time, though, ajumma has gathered more meaning — and more judgment — than the dictionary suggests.

Women today often hesitate to be called ajumma. The word conjures a vivid image: short perm, floral pants, large sun visor, strong opinions. She’s the woman running a market stall or rushing through the subway, the mother juggling everyone else’s needs before her own. But it also evokes camaraderie, solidarity, and an unspoken dedication to those she considers “family.”

In the open, usually Ajummas move in packs. Walk through any traditional market and you’ll see rows of bright patterned pants and shirts — the unofficial ajumma uniform. On sunny days, the visors go on, wide and practical, hiding half their faces as they go about their business.

Still, they are often mocked: too loud, too pushy, too plain. Their perceived lack of fashionable femininity has even earned them the nickname “a third gender.”

How the name became a stigma

In modern Korea, “Ajumma” has slipped from a neutral label to a near-insult. It suggests someone unfashionable, outspoken, maybe even coarse — a woman past her social “prime.” Technically, any married woman could be called ajumma, but the term has aged with the generation of grandmothers and mothers who built contemporary Korea.

Today, many women flinch when addressed that way. Yet in a society where every interaction demands an honorific, removing the word ajumma leaves a linguistic gap. What do you call a woman older than you but not elderly, who is neither your boss nor your mother? Alternatives like ajumeoni, eomonim (“someone else’s mother”), samonim (“madam”), or even “house manager” have emerged — none quite replacing the original.

The shame reveals something larger: a culture still uneasy with visible, middle-aged women — especially those who don’t display gentleness or glamour.

As Wikipedia (1) notes, Korean feminists argue that ajumma’s low status reflects broader sexism and classism — the idea that a woman’s worth is still tied to her youth, beauty, and docility. Yet these women are also Korea’s mothers, whose modest lives have quietly underpinned the nation’s success.

Unjustly Infamous

On Reddit, I once stumbled upon a thread where people described the ajummas around them with humor and fondness rather than disdain.

“I’m a Korean in the US who just turned 30. When I walk the dog in the morning I wear a visor and puffer jacket — it’s early-onset ajumma! I even cut my hair short for practicality. No perm yet, but give it time.”

Another wrote:

“My wife is in her mid-40s and has been wearing the floral pajama pants for ten years. Two visors, several puffer jackets that become vests in spring… She’s on her way.”

And from a travel blog:

“My first day in Korea, an ajumma — a complete stranger — insisted on using her phone to call my new boss. She patted my arm, smiled, made sure I had a ride, then boarded the bus by pushing her way to the front of the line.”

The tone is teasing, yes, but with affection. Beneath the laughter sits recognition: Ajummas are tough, blunt, almost comic in their ways but also dedicated and resilient.

The spirit behind the stereotype

Yet behind the caricature there is a history of endurance.

The ajumma generation helped rebuild Korea from post-war poverty to high-tech prosperity. They worked in factories, sold in markets, raised children who became engineers, artists, and CEOs. Their thrift, resourcefulness, tenacity, and refusal to quit fueled the country’s rise.

They are the ones who learned to stretch a single paycheck, to feed five mouths, to push through fatigue because someone had to. The country’s dazzling skyline rests, in part, on ajumma grit.

Their manner may seem harsh, but it’s the language of tough love — care expressed through challenge. An ajumma doesn’t coddle; she believes that protecting someone means preparing them for reality. She’ll cook you soup when you’re sick, then tell you to get up and face the world. An ajumma doesn’t coddle; she cares through challenge. Her affection often sounds like, “You can do better. I know because I’ve seen what you can take.”

From Mockery to Respect

Yes, some ajummas shove on the subway or speak bluntly. But that bluntness is often the echo of a lifelong struggle — the shorthand of women who’ve carried the weight of everyone else’s economic, physical, and emotional well-being.

When we criticize their lack of manners, we forget how many hours they’ve spent supporting families, keeping small businesses afloat, and holding neighborhoods together.

When we smile at their visors and floral pants, we miss their essential role — pillars of a society built on endurance and care.

Maybe it’s time to stop replacing the word ajumma with something more “modern.”

Maybe sleek, global Korea could afford to remember the women who remain its backbone.

It’s telling that the floral pants — once a symbol of unfashionable practicality — are now reappearing on young women, worn ironically or proudly. Perhaps the cycle of respect is slowly turning back.

Let’s revive the fierce, brave spirit of the Ajumma —

not as a relic of the past, but as a living reminder that care, grit, and courage often wear comfortable shoes.

As a French coach living in Seoul, I often look at culture through the lens of everyday leadership — how ordinary people lead through care, grit, and quiet perseverance. The ajumma embodies that perfectly. Writing this piece is my small tribute to the women whose invisible strength helped build modern Korea — and who, even today, keep it running with unshakable resolve.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ajumma

- https://www.reddit.com/r/korea/comments/12pgnsv/i_found_this_picture_while_researching_the/

- https://pinkpangea.com/2012/12/south-koreas-unjustly-infamous-ajumma/

- Illustration by Amy Slatem : https://artaims.wordpress.com/2017/03/23/the-ajumma-starter-kit/

Bénédicte / The Great Floating Tribe